Mona Ali Khalil女史: 国連がすべての平和維持要員の安全を確保することを勧告した『クルーズ報告書』は、攻撃的で過大な武力行使を推進し国連PKO部隊が紛争の当事者になることを容認している。(彼女の記事はこちら)

モナ・アリ・カリル(Mona Ali Khalil)女史は、UNの平和維持活動は、民間人に対する攻撃や国連の要員、財産、施設に対するしての脅威に予防的かつ決定的に積極な行動をとらなければならないが、圧倒的で積極的な軍事力の使用を国連の平和維持軍に求めるべきではないと言う。その理由として三つ挙げている。

第一には、国連は、ある特定の国の軍隊に武力行動を命じ、別の国の平和維持のために命を落とすこと要求することになる。そのような状況下で究極の犠牲を払う意欲は、守るべき平和がないときには維持するのが難しい。戦闘行為に積極的に参加するように軍の貢献を求めることは、公平性を破り、平和活動を妨げ、脆弱性を減らすよりもむしろ増加する可能性が高い。国連の平和維持活動は、自衛権と民間人の人権の保護という固有の権利を損なうことなく、成功した戦力ではなく平和の公平な代理人であることをより重視すべきである。したがって、国連の人員や一般市民の安全を保障することが、平和維持者としてではなく、平和維持者としてよりも有用であることは、平和維持活動を提案する上でより積極的で、平和協議を当事者にもたらす上で積極であるべきである。

第二には、法的問題として、「圧倒的な力」を使用することは、許可された軍事目的を達成するために必要で適当で最小限の武力の使用に関する国連が関与するにあたっての規則に反することなく施行すべきである。

第三には、圧倒的な軍事力を使用するよう国連の平和維持活動に要請することは、国際人道法の下での紛争の当事者となる可能性を高める。クルーズ報告書は、現在の平和維持活動が少なくとも1度は紛争の当事国となっていることを認識していない。国連の平和維持部隊がM23民兵に対して積極的な作戦で攻撃した結果、コンゴの国連ミッション(MONUSCO)は紛争の当事者となってしまった。その結果、国連平和維持部隊は保護された地位を失い、国際人道法のもとで正当な軍事行動の対象になったのである。

クルーズ報告書は、軍隊の積極的な行動の法的な結果を無視することによって、国際人道法の国連ミッションとしてのMONUSCOへの適用可能性について、安全保障理事会が独自に無視したことを反映している。報告書は、国連の平和維持活動に対するすべての攻撃を「戦争犯罪」と呼んでいるが、安保理は、こうした攻撃の計画、指揮、または実施をすることを第7章の制裁活動を継続して扱っている。

モナ・カリル女史は、これらの点に関する理事会の特権を損なうことなく、また、その決議が国際人道法を尊重することをすべての締約国に求めている限り、国際人道法の意味を明確に理解することは、国連部隊が直接に攻撃に晒され、保護しようとしている民間人に大きな脅威を与えてしますと説いている。そして、最後にクルーズ報告書は国連の平和維持部隊への犯罪の説明責任を要求しているが、国連の平和維持部隊員自身が犯した犯罪については説明責任を負わないでいる。性的犯罪を含む国連平和維持軍の部隊の犯罪に対する刑事責任の欠如は、国連平和維持活動の信頼と正当性を明らかに低下させ、平和維持軍の攻撃に対して立場をより脆弱にしてしまうと言えよう。

The UN’s Cruz Report on Improving Peacekeepers’ Security Goes Too Far

Since 1999, the United Nations Security Council has consistently entrusted its peacekeeping operations with clear authority to use force beyond self-defense — primarily for the protection of civilians. To fulfill the mandate, the Council expects UN peacekeeping forces to take preventive as well as responsive actions; to proactively patrol the local communities; to project a strong deterrent posture; and to be robust in defending themselves and protecting civilians.

For too long, however, there has been a clear gap between expectation and performance. Despite the failures, the Council now expects UN forces to conduct strategic and ever more aggressive operations to help stabilize increasingly hostile environments and to neutralize insurgents in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, terrorists in Mali and government forces in South Sudan.

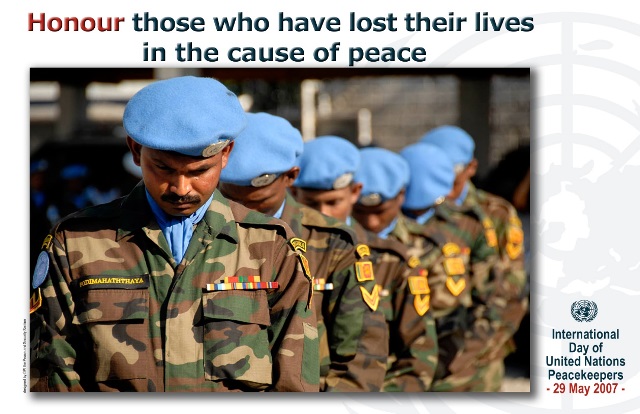

The rising death toll among UN peacekeepers is one of many consequences of UN engagement with such actors in such environments.

In the UN’s recently published Cruz report, “Improving the Security of UN Peacekeepers,” Lt. Gen. Carlos Alberto dos Santos Cruz and his fellow authors note that 195 personnel have been killed by violence since 2013, “more than during any other 5-year period in history” — and that 56 of them were killed in 2017 alone — “the highest number since 1994.”

The authors proceed to set out concrete and comprehensive recommendations on how the UN can improve the security of UN peacekeepers. By calling on UN peacekeepers to use “overwhelming force,” as opposed to robust defensive or protective force, the Cruz report may have gone too far, potentially undermining the security of both UN personnel and the civilians they are meant to protect. (A UN Security Council session on protecting civilians in armed conflict is scheduled for May 22.)

While UN peace operations must be proactive in preventing and decisive in responding to attacks on civilians and against UN personnel, property and premises, UN peacekeepers should not be called on to use overwhelming or aggressive force.

Here is why:

First, the UN calls on the troops of one country to fight and possibly die for the cause of peace in another country. The willingness to make the ultimate sacrifice under such circumstances is already difficult to achieve when there is no peace to keep. Calling on the troops to actively participate in warlike behavior will destroy their impartiality, hinder their peace efforts and more likely increase rather than decrease their vulnerability. Without prejudice to its inherent right of self-defense and its protection of civilian mandate, a UN peacekeeping operation should be more concerned about being an impartial agent of peace rather than as a successful force of war. It may therefore be far better for the security of UN personnel and civilians alike for peacekeepers to be more useful as peacemakers rather than as peace enforcers — to be more proactive in proposing peace plans and more aggressive in bringing parties to peace talks.

Second, as a legal matter, using “overwhelming force” may constitute excessive force, contravening the standard UN rules of engagement on the use of targeted, proportionate, graduated and minimum force necessary to achieve the authorized military objective.

Third, calling on UN peacekeeping operations to use overwhelming force also increases the likelihood of their becoming parties to the conflicts under international humanitarian law. The Cruz report does not take into account that, at least once, a current peacekeeping mission has become a party to the conflict. As a result of aggressive operations that its forces have conducted against the M23 militia, the UN mission in the Congo, called Monusco, has become a party to the conflict in the country. As such, its forces have lost their protected status and have become legitimate military targets under international humanitarian law.

By ignoring the legal consequences of using aggressive force, the Cruz report has mirrored the Security Council’s own disregard for the applicability of international humanitarian law to Monusco. The report insists on referring to all attacks on UN peacekeeping operations as “war crimes” while the Council continues to impose Chapter VII sanctions on those planning, directing or conducting such attacks.

Without prejudice to the Council’s prerogatives in this regard, and to the extent that its resolutions call on all parties to respect international humanitarian law, a clear understanding of IHL’s implications is necessary to ensure that UN forces are aware of the loss of their protected status under the law and that, as such, they become exposed to direct attack and thus pose a greater threat to the very civilians they are meant to protect.

Lastly, while the Cruz report calls for accountability for crimes against UN peacekeepers, it fails to call equally for accountability for crimes committed by UN peacekeepers. The lack of criminal accountability for the latter crimes — including sexual crimes — has demonstrably diminished the credibility and legitimacy of UN peacekeeping operations in the hearts and minds of the local populations they are supposed to protect, further increasing peacekeepers’ vulnerability to attack.

This article first appeared on PassBlue and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.