UN report on improving the security of all peacekeepers is viewed as pushing overwhelming and aggressive operations making the UN party to conflict and potentially undermining the security of both UN personnel and the civilians they are meant to protect. Here is her article.

Mona Ali Khalil is an internationally recognized public international lawyer with 25 years of UN and other global experience in peacekeeping, sanctions, disarmament and counterterrorism. She holds a B.A. and an M.A. from Harvard University and a master’s degree in foreign service and a juris doctorate from Georgetown University. She is an affiliate of the Harvard Law School Program on International Law and Armed Conflict and is a former senior legal officer in the UN Office of the Legal Counsel. In January 2018, Khalil founded MAKLAW.ORG, an international legal advisory and consulting service, assisting governments and nongovernmental organizations to secure their rights and fulfill their legal obligations.

Former Special Representative of the Secretary-General Martin Kobler in the Democratic Republic of Congo and Head of the United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of Congo (MONUSC) has contested Miss Mona Khalil`s assertion that the Cruz report went too far. He worked with General Cruz and believes that the UN is impartial when it comes to politics, but the UN should not be “neutral” when it comes to human rights violations. According to him, the UN must become a party to protect human rights of people particularly women and children. UN peacekeepers cannot stand idle when massacre happens.

In clarifying her position, Mona Khalil explains that it does not have to be an issue of all or nothing. UNPKO forces can and should fully and robustly use force in self-defense and for the protection of civilians – against hostile actors and hostile acts especially in the face of such atrocities as have been committed in places like DRC, South Sudan, Mali and CAR. However, she maintains that the efficacy of using force that is necessary and proportionate to achieve the legitimate military objectives; the use of force should not be aggressive and overwhelming to be credible and effective.

The UN’s Cruz Report on Improving Peacekeepers’ Security Goes Too Far

Since 1999, the United Nations Security Council has consistently entrusted its peacekeeping operations with clear authority to use force beyond self-defense — primarily for the protection of civilians. To fulfill the mandate, the Council expects UN peacekeeping forces to take preventive as well as responsive actions; to proactively patrol the local communities; to project a strong deterrent posture; and to be robust in defending themselves and protecting civilians.

For too long, however, there has been a clear gap between expectation and performance. Despite the failures, the Council now expects UN forces to conduct strategic and ever more aggressive operations to help stabilize increasingly hostile environments and to neutralize insurgents in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, terrorists in Mali and government forces in South Sudan.

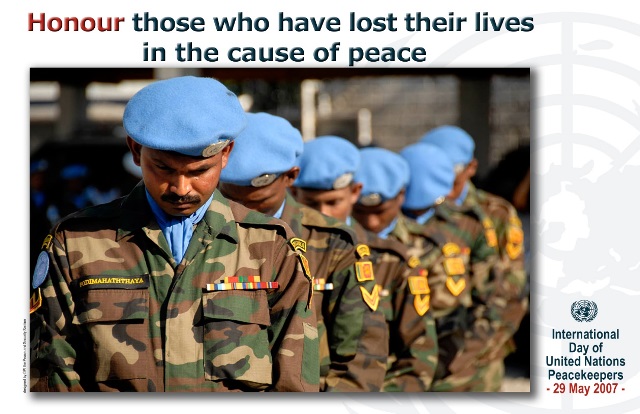

The rising death toll among UN peacekeepers is one of many consequences of UN engagement with such actors in such environments.

In the UN’s recently published Cruz report, “Improving the Security of UN Peacekeepers,” Lt. Gen. Carlos Alberto dos Santos Cruz and his fellow authors note that 195 personnel have been killed by violence since 2013, “more than during any other 5-year period in history” — and that 56 of them were killed in 2017 alone — “the highest number since 1994.”

The authors proceed to set out concrete and comprehensive recommendations on how the UN can improve the security of UN peacekeepers. By calling on UN peacekeepers to use “overwhelming force,” as opposed to robust defensive or protective force, the Cruz report may have gone too far, potentially undermining the security of both UN personnel and the civilians they are meant to protect. (A UN Security Council session on protecting civilians in armed conflict is scheduled for May 22.)

While UN peace operations must be proactive in preventing and decisive in responding to attacks on civilians and against UN personnel, property and premises, UN peacekeepers should not be called on to use overwhelming or aggressive force.

Here is why:

First, the UN calls on the troops of one country to fight and possibly die for the cause of peace in another country. The willingness to make the ultimate sacrifice under such circumstances is already difficult to achieve when there is no peace to keep. Calling on the troops to actively participate in warlike behavior will destroy their impartiality, hinder their peace efforts and more likely increase rather than decrease their vulnerability. Without prejudice to its inherent right of self-defense and its protection of civilian mandate, a UN peacekeeping operation should be more concerned about being an impartial agent of peace rather than as a successful force of war. It may therefore be far better for the security of UN personnel and civilians alike for peacekeepers to be more useful as peacemakers rather than as peace enforcers — to be more proactive in proposing peace plans and more aggressive in bringing parties to peace talks.

Second, as a legal matter, using “overwhelming force” may constitute excessive force, contravening the standard UN rules of engagement on the use of targeted, proportionate, graduated and minimum force necessary to achieve the authorized military objective.

Third, calling on UN peacekeeping operations to use overwhelming force also increases the likelihood of their becoming parties to the conflicts under international humanitarian law. The Cruz report does not take into account that, at least once, a current peacekeeping mission has become a party to the conflict. As a result of aggressive operations that its forces have conducted against the M23 militia, the UN mission in the Congo, called Monusco, has become a party to the conflict in the country. As such, its forces have lost their protected status and have become legitimate military targets under international humanitarian law.

By ignoring the legal consequences of using aggressive force, the Cruz report has mirrored the Security Council’s own disregard for the applicability of international humanitarian law to Monusco. The report insists on referring to all attacks on UN peacekeeping operations as “war crimes” while the Council continues to impose Chapter VII sanctions on those planning, directing or conducting such attacks.

Without prejudice to the Council’s prerogatives in this regard, and to the extent that its resolutions call on all parties to respect international humanitarian law, a clear understanding of IHL’s implications is necessary to ensure that UN forces are aware of the loss of their protected status under the law and that, as such, they become exposed to direct attack and thus pose a greater threat to the very civilians they are meant to protect.

Lastly, while the Cruz report calls for accountability for crimes against UN peacekeepers, it fails to call equally for accountability for crimes committed by UN peacekeepers. The lack of criminal accountability for the latter crimes — including sexual crimes — has demonstrably diminished the credibility and legitimacy of UN peacekeeping operations in the hearts and minds of the local populations they are supposed to protect, further increasing peacekeepers’ vulnerability to attack.

This article first appeared on PassBlue and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.